Cruciate Injury

Cruciate Ligament Injury is the term used to describe any sprain, partial tear or more commonly, complete rupture (where the ligament is completely torn) of the Cruciate Ligament, inside the dog (or cat) knee.

Cruciate Ligament Injury is the term used to describe any sprain, partial tear or more commonly, complete rupture (where the ligament is completely torn) of the Cruciate Ligament, inside the dog (or cat) knee.

Cruciate Ligament Injury is an important cause of lameness in the dog, and can lead to permanent severe lameness, and/or debilitating arthritis, if not managed or treated correctly.

What is the Cruciate Ligament, and why is it so important?

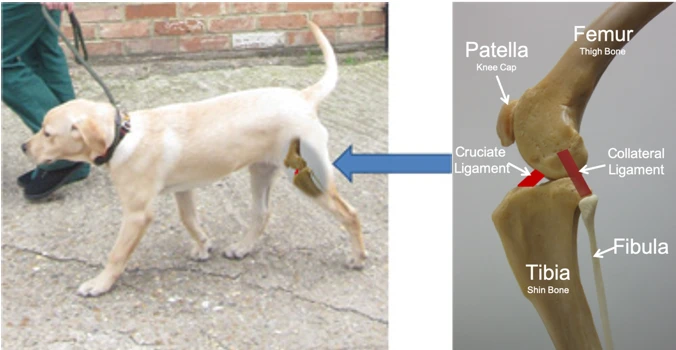

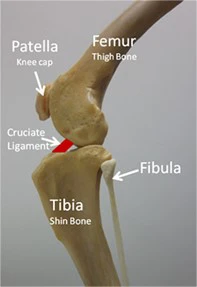

The knee joint (or stifle as it is known in animals) is principally a hinge joint between the femur (thigh bone) and the tibia (shin bone). The knee joint is held together by a number of strong ligaments, including the collaterals and the cruciates (see diagram).

The Medial and lateral collateral ligaments prevent the knee from hinging from side to side, and the cruciate ligaments prevent the tibia sliding backward and forward with respect to the femur.

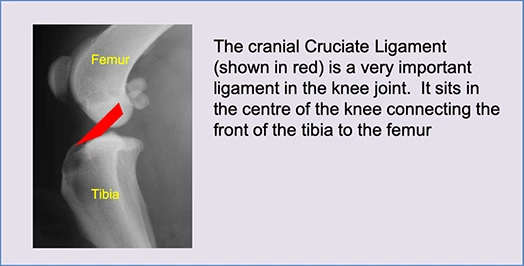

In the diagram below, a radiograph (x-ray) shows the femur and tibia in their normal positions with the cranial Cruciate Ligament shown in red.

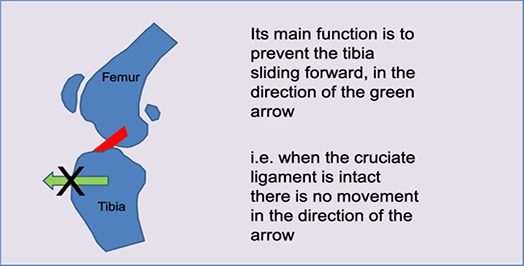

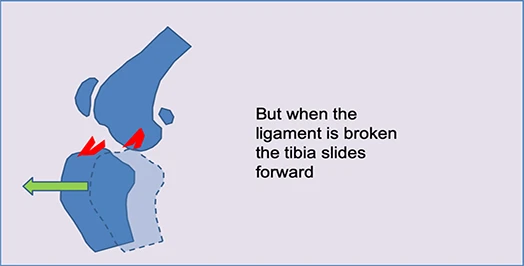

The outline drawings below shows that the main function of the cranial cruciate ligament is to prevent the tibia sliding in the direction of the green arrow.

If the ligament is broken the tibia slides forward when the animal bears weight. This sliding movement causes pain and inflammation in the joint. The pain will obviously cause lameness, and persistent inflammation can be associated with progression of arthritis in the joint, which can lead to permanent disability.

Typical signs of lameness associated with Cruciate Injury

Lameness associated with cruciate injury can be sudden in onset (for instance if your dog tears the cruciate at exercise), but can also be slower in onset if gradual deterioration and breakdown of the ligament occurs.

In fact what commonly happens is a mixture of both of the above, whereby you observe a gradual onset intermittent low-grade lameness, followed by a sudden onset of more severe lameness when the ligament breaks.

Typically during the early low-level lameness your dog will only be stiff when getting out of bed, or after lying down. Lameness eases up during exercise and very often lameness is forgotten altogether if the dog is distracted (i.e. chasing a squirrel). The stiffness after rest will often be worse following a period of increased exercise.

In long standing cases of cruciate injury you may notice loss of thigh muscle in the affected limb. Animals with cruciate injury will often “unweight” the injured leg, by standing with more weight on the good leg. You may notice the sore leg positioned slightly to the side of the body, with the paw not placed fully on the ground.

It is important to realise that these are typical signs associated with cruciate injury. Individual cases may present quite differently, and other causes of hind-limb lameness (i.e. hip injury or hip arthritis) can present in a very similar manner.

How do we treat Cruciate Injury?

How we choose to treat cruciate injury will depend on several factors including:

- The degree of damage to the ligament

- The size and weight of your dog

- The type of lifestyle/activity etc.

Low-grade Injury i.e. simple sprain

In the same way we might treat a sprained ankle in ourselves, simple ligament sprain can often be treated by a short period of rest and the use of anti inflammatories.

Rest can vary between total restriction of all activity (i.e. cage confinement and lead walking only in the garden for toilet purposes), or can simply mean moderation of exercise (i.e. “house arrest” and only 10-15 minutes lead walking once or twice per day).

If lameness resolves then gradual return to exercise is advised. Gradual build-up of exercise is extremely important. Too rapid a return to too much exercise can result in recurrence or even worsening of ligament injury.

Severe Injury/Complete Ligament Rupture

Treatment of more significant cruciate injury can be confusing. There are a large number of different surgical techniques, management options, and even more varied opinions as to how these should be implemented.

Broadly…..

- Smaller <15kg less active dogs (and some less active larger older dogs) can possibly be managed successfully without surgery.

- Heavier >15kg, more athletic, dogs usually require surgery.

There are breed exceptions, with certain small breeds often requiring a surgical solution (see later).

Smaller dogs (less than 15kg body weight)

A large number of dogs (and cats) less than 15kg body weight can be managed conservatively. This means surgery should not be required. In these animals fibrosis and scarring of the damaged joint, and recruitment of thigh muscles, is sufficient to stabilise the knee, and prevent the sliding movement described above.

A large number of dogs (and cats) less than 15kg body weight can be managed conservatively. This means surgery should not be required. In these animals fibrosis and scarring of the damaged joint, and recruitment of thigh muscles, is sufficient to stabilise the knee, and prevent the sliding movement described above.

Conservative management will often require several weeks of very strict rest and may take 2-3 months to achieve near normal function. This can appear very frustrating as recovery often appears to be slow.

A small number of dogs weighing less than 15kg will not respond to conservative management, and will go on to require surgery.

Advantages of conservative management:

- Avoids any risk of surgery

- Often successful in small dogs and cats

Disadvantages of conservative management:

- Final recovery to normal or near normal function may not ever be quite achieved

- No opportunity to examine joint surgically to assess other injuries (ie cartilage tear)

NB. It must be borne in mind that whilst surgery may appear to be a quicker solution, in reality the strict post-surgical rest period and recovery/physiotherapy schedule can be as long as conservative management.

Larger Dogs (more than 15kg body weight)

It is generally accepted that the majority of dogs weighing more than 15kg will require some sort of surgical treatment. Older less active dogs may still be able to be managed conservatively but recovery is usually prolonged (see above)

It is generally accepted that the majority of dogs weighing more than 15kg will require some sort of surgical treatment. Older less active dogs may still be able to be managed conservatively but recovery is usually prolonged (see above)

Advantages of surgical management:

- Facilitates surgical examination of joint to assess other injuries (ie cartilage tear)

- Final recovery usually nearer to normal function

- Higher overall success rate

Disadvantages of surgical management:

- Involves a surgical procedure

Surgical Correction of Cruciate Injury

There are a large number surgical treatments that have been tried historically, and many are still used. The majority opinion now favours two broad disciplines of surgical repair:

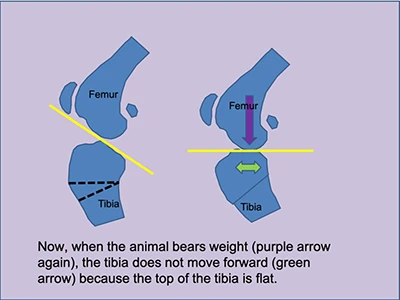

1. Altering the geometry of the weight bearing angle of the top of the tibia, so the tibia doesn't tend to slide forward during weight bearing.

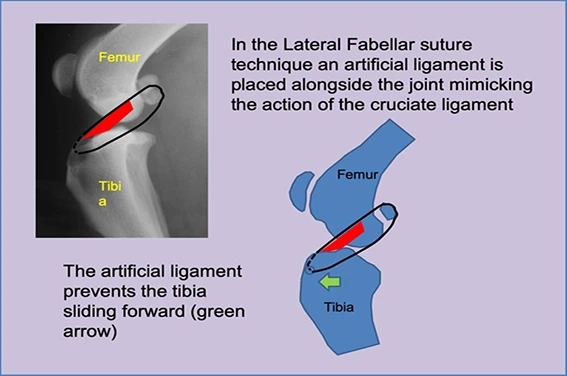

2. Stabilising the knee using an artificial replacement ligament, either inside the knee, or alongside the knee, mimicking the action of the original cruciate ligament.

Tibial Plateau Levelling Osteotomy TPLO (including Slocum or Radial TPLO and Closing Wedge Osteotomy CWO)

In these techniques the inside of the joint is first examined to confirm that the cruciate ligament is broken. Next the condition of the cartilages (sometimes called menisci) within the knee is carefully assessed. If the menisci are damaged then surgical removal of the damaged portions is performed.

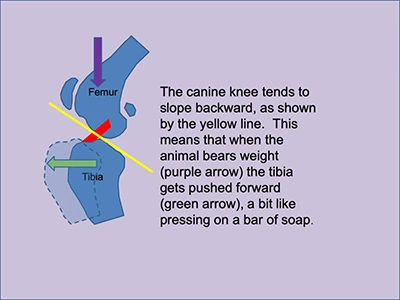

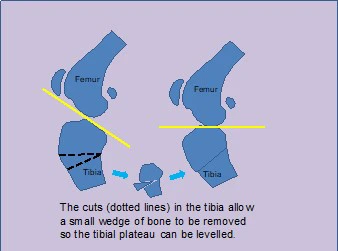

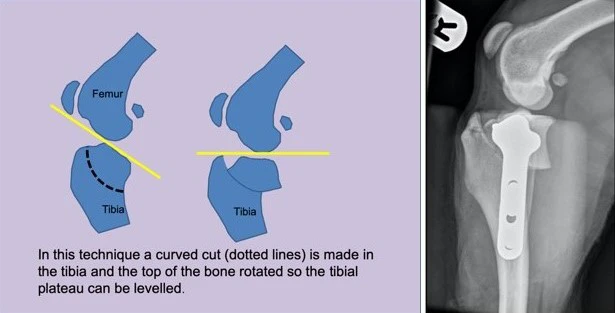

All the TPLO techniques work by altering the standing angle of the knee join by cutting and altering the angle of the top of the tibia (shin bone) immediately below the knee joint itself. The top of the tibia in the dog, tends to slope backwards, which means the tibia will slide forward when the animal bears weight (see diagram below). The intact cruciate prevents this sliding motion, as described above.

In its simplest form TPLO is performed as a 'Closing Wedge' where a triangular wedge of bone is removed from just below the joint surface. Collapsing the wedge, reduces the backward slop of the top of the tibia so that weight bearing no longer causes the tibia to slide forward.

When the wedge is closed, the bone is held in place with a plate as shown in the radiograph.

A more elegant version of the TPLO, and arguably the gold standard with respect to cruciate surgery, it involves a curved cut in the tibia so that the top of the tibia can be rotated to reduce the joint angle. This is the 'Slocum' or 'Radial Cut' TPLO. This is our preferred technique at Hall Place Veterinary Centre.

The specific type of TPLO will depend on a number of factors including the size and weight of your dog.

Other techniques include a different type of bone cut which allows the front of the tibia to be pushed forward. These include the Tibial Tuberosity Advancement (TTA) and Modified Machet Procedure (MMP).

Lateral Fabellar Extracapsular Suture

In this technique the inside of the joint is examined to confirm that the cruciate ligament is broken and to check the condition of the cartilages (sometimes called menisci) within the knee. If the menisci are damaged they may be repaired or the damaged portions removed.

An artificial replacement ligament (usually made of monofilament nylon or other braided synthetic material) is placed in a position that mimics the action of the original cruciate ligament (see diagram).

It is important to realise that this technique does not actually repair the broken cruciate ligament, nor does the replacement ligament last forever. Rather, it works by replacing the function of the cruciate ligament long enough for the animal to learn to stabilise its own knee, by a combination of fibrosis and scarring of the joint, and by the correct use of its thigh muscles. In practice, this technique is not considered as successful as the TPLO techniques.

Terriers and West Highland Terriers

A number of the terrier breeds, including the Jack Russell and, in particular, the West Highland White Terriers have an extremely marked backward slop to the tibial plateau. This predisposes them to cruciate injury and is probably, at least partly responsible, for a poor response to conservative management in these breeds. For this reason, we very often recommend a TPLO procedure in these animals despite their small size.

A number of the terrier breeds, including the Jack Russell and, in particular, the West Highland White Terriers have an extremely marked backward slop to the tibial plateau. This predisposes them to cruciate injury and is probably, at least partly responsible, for a poor response to conservative management in these breeds. For this reason, we very often recommend a TPLO procedure in these animals despite their small size.

Rehabilitation following Cruciate Injury

Rehabilitation following cruciate injury and/or following surgical repair involves a carefully controlled program of restricted activity followed by gradually increased exercise, physiotherapy, and can include other physiotherapy type activities including hydrotherapy.

Each animal is unique and, in practice, each animal requires a bespoke rehabilitation program. We give specific advice based on your dog’s requirements. The following is a broad outline of routine advice following surgical stabilisation of cruciate injury in the dog.

Immediate post-operative period (Day 0 - 3 weeks)

Immediate post-operative period (Day 0 - 3 weeks)

The majority of animals will be non-weight bearing for the first 24-36hrs following surgery, but will gradually start to place the foot more and more each day. The aim of the first 3 week post-operative period is to restrict exercise to allow repair of the damage and inflammation caused by the ligament injury, and to allow repair of the surgery.

Strict Rest

Strict rest means almost as little activity as possible, with lead walking only in the garden, or wherever appropriate, for toilet purposes only. It is important to maintain lead control even in the garden because animals can become distracted (eg squirrels, birds etc) and attempt to run on an operated leg long before it is strong enough to withstand this. In a worse case this can cause catastrophic damage.

Toward the end of the three week period, provided walking is improving gradually, more activity can be allowed.

Ice Compresses

Ice and cooling are probably beneficial, at least in the immediate post-operative period, and are certainly known to be of great value in human patients following surgery. Provided your pet will tolerate application, ice or frozen peas can be used to gently cool the tissues around the joint. Ice etc should never be applied direct to the skin, but rather behind a cloth or towel. Repeated application of short duration is usually better tolerated and application should never exceed 10mins.

3-6 weeks

The majority of animal will be weight bearing well at 3 weeks post-op, but still obviously lame. We advise the following three exercises during the next 3 weeks:

A 5 minute walk, twice daily, increased by 1 minute each day.

This is lead walking only, and must be done at a speed slow enough that your dog walks as near to normally (ie without limping) as possible. At the start of this period your dog will probably be able to move much faster if allowed to limp along, but it is important to re-“teach” your dog to walk properly.

This is lead walking only, and must be done at a speed slow enough that your dog walks as near to normally (ie without limping) as possible. At the start of this period your dog will probably be able to move much faster if allowed to limp along, but it is important to re-“teach” your dog to walk properly.

Provided your dog is not lame at the end of the 5minute walk AND provided your dog is not unduly stiff that evening OR the following day, then the walk can be increased by a minute each day. If you dog does become more lame, or stiff, then walk will have to remain at current level or even be reduced. Provided all goes well, each walk should be 20-25minutes long by the end of the 3 week period.

Sit Stand Exercises

Sit Stand Exercises

A large number of dogs do not sit properly even under normal circumstances, and will often “slouch” with one or both hind limbs turned under or away from the body. Following knee surgery your dog will usually try to sit with the operated leg straight and angled away from the body. It is difficult to get dogs to go to the gym and do leg squats!, but we can attempt to teach them to sit properly so that the stifles (knees) are properly flexed and square to the dog. This not only flexes the knee correctly but it means the dog will use the leg when getting up, rather than solely using the other hind limb.

Not all dogs can be trained to sit properly, particularly if they have never done it, and it usually takes several days or more to make progress. You may need to use a new command such as “neat sit” or train your dog to sit between your feet, and gradually make the gap smaller.

Not all dogs can be trained to sit properly, particularly if they have never done it, and it usually takes several days or more to make progress. You may need to use a new command such as “neat sit” or train your dog to sit between your feet, and gradually make the gap smaller.

Passive Motion

Following surgery the range of motion of the joint (the degree to which the joint can comfortably be flexed and extended) will often be reduced. Unwillingness to flex or extend the joint can be a source of continued lameness. The range of motion of the joint can be increased by gently cycling the joint through its normal range. This also stimulates the thigh muscles. This can be done with your dog lying down or standing. 10-12 cycles twice daily is usually sufficient.

6-10 weeks

The majority of animals will be walking and trotting very well by this stage, but often still uneven in gait at a faster trot. They usually have significantly reduced leg muscle following prolonged lameness and lack of use of the limb following surgery. The aim of the next four weeks exercise, is to re-build fitness and regain lost muscle.

Gradually Increased Exercise

This initially starts as continuing the twice daily walks but increasing the pace of parts of the walk. Initially this may simply take the form of using a flexi lead so that your dog can run a short distance past you BUT, you are still in control. Running or jogging yourself can be useful, or even using a bike, provided your dog is sensible. Early in this stage, the periods of faster pace should be short but should be increased in both intensity and duration as progress is made. One size does not fit all and it is important for you to work out how best to gradually increase the tempo of your individual dogs exercise.

10 weeks+

The majority of animals will be trotting almost normally by this stage and will have recovered a significant amount of lost muscle. The aim of the next stage is transition/return to “normal” exercise.

There are a large number of variables at this point including the progress made over the previous weeks, the demeanour of the dog, and what “normal” exercise actually means. This means that a “sensible” dog that has made very good progress, and didn’t used to do a lot of exercise anyway, is almost completely recovered, and can be returned to normal activity quite quickly. On the other hand a less controlled dog, that has not made such a good recovery, but is used to uninhibited exercise in difficult terrain will have to be much more carefully managed.

The challenge is to transition from the controlled faster paced activity of the previous weeks, to off lead exercise, without your dog damaging the joint by excessive activity. What we are trying to achieve is increasingly faster and harder exercise, but still all under controlled conditions. The analogy is a footballer returning from injury who will rehabilitate by running faster and harder on a treadmill or a smooth road surface, but who will not play football itself for a long time. The key concept is (as above) that one size does not fit all, and the placid Labrador who trots round and smells the flowers can be let off lead well before the lunatic, who will complete 5 circuits of the park within 30seconds of release. You know your dog and you have to devise a plan to achieve the required transition.

The challenge is to transition from the controlled faster paced activity of the previous weeks, to off lead exercise, without your dog damaging the joint by excessive activity. What we are trying to achieve is increasingly faster and harder exercise, but still all under controlled conditions. The analogy is a footballer returning from injury who will rehabilitate by running faster and harder on a treadmill or a smooth road surface, but who will not play football itself for a long time. The key concept is (as above) that one size does not fit all, and the placid Labrador who trots round and smells the flowers can be let off lead well before the lunatic, who will complete 5 circuits of the park within 30seconds of release. You know your dog and you have to devise a plan to achieve the required transition.